- Remembering Mark Wiener

- What’s Fermenting: Beet Kvass

- Carnegie Hall Opening Night

- Flatiron: SONA

- Recipe: Zucchini Pancakes – Placki z Cukinii

- Recipe: Vegan Sichuan Inspired Celery Stir Fry

- Recipe: 48 Hour Sourdough Focaccia

- Recipe: Rye and Whole Wheat Sourdough Bread

- Recipe: Sourdough Crackers

- Recipe: Easy Kimchi Pancakes

- Midtown East: A Final Visit to (Burger) Heaven

- Miami: L’Atelier de Joël Robuchon

- Recipe: Viennese Krautfleckerl (Pasta & Cabbage)

- Midtown East: Le Veau d’Or & Céleri Rémoulade

- TriBeCa: Lekka Burger

- Friday at five: The Rusty Nail

- Friday at five: The Robert Burns

- How We Compost in NYC

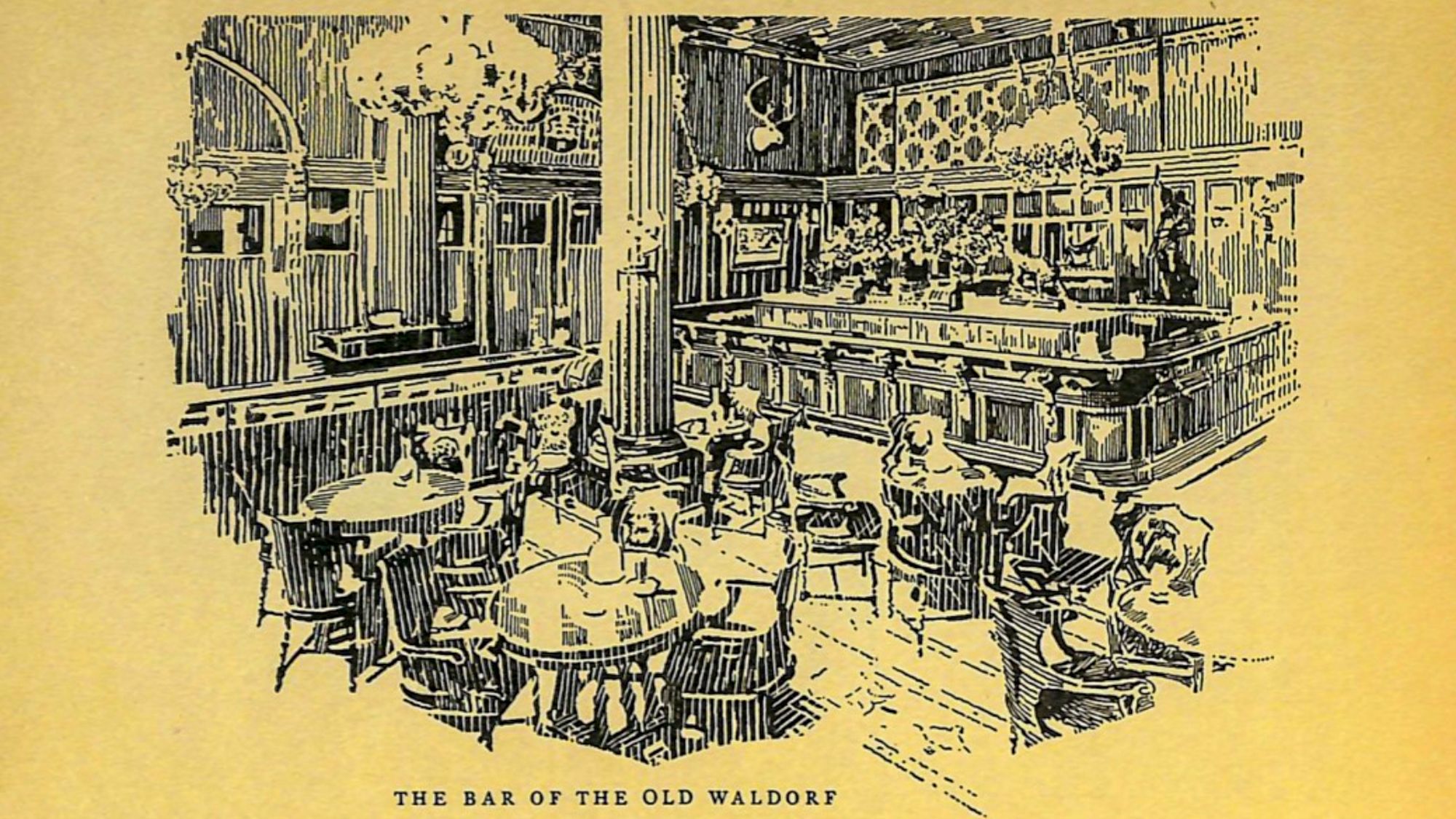

- Friday at five: Rob Roy

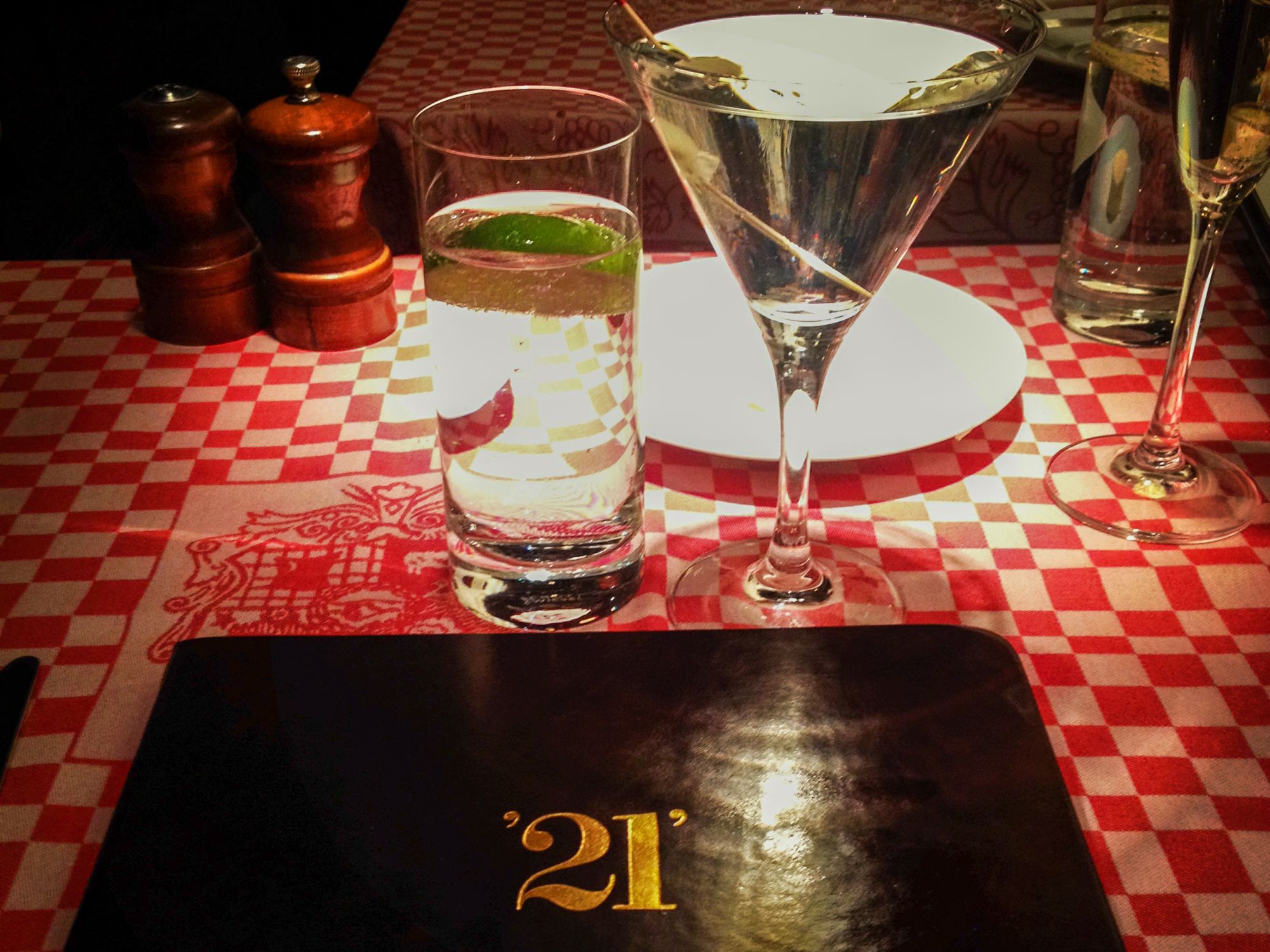

- Friday at five: The Gibson

- Midtown East: La Pecora Bianca

- Friday at five: Rye and Ginger

- What's fermenting: Easy Homemade (Vegan) Kimchi

- Midtown East: TacoVision

- Friday at five: Old Pal

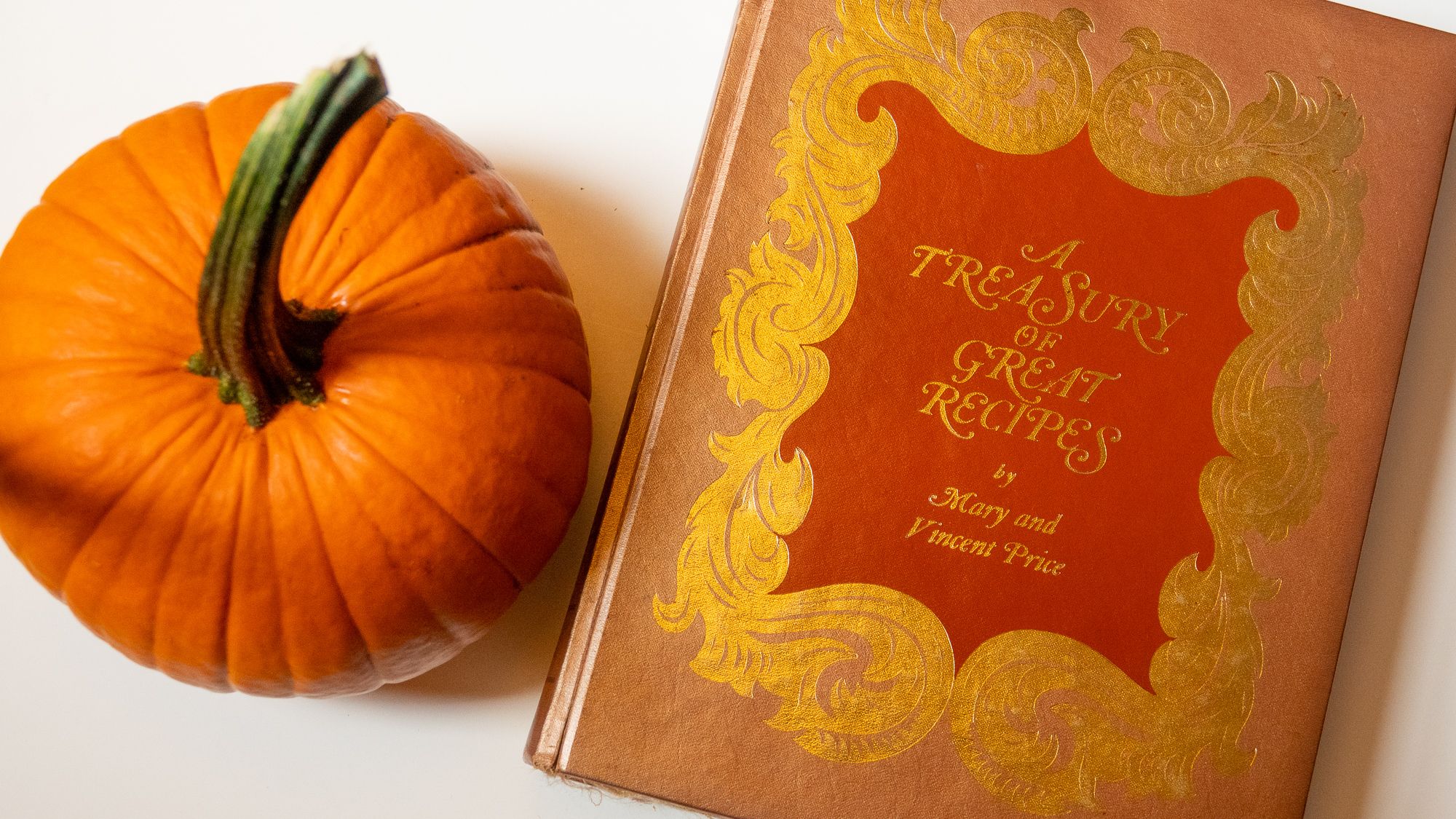

- Vincent Price, Horror Actor...Cookbook Author

- What's fermenting: Union Square Greenmarket Sauerkraut

- Friday at five: Sazerac

- Homemade Yogurt the Sous Vide Way

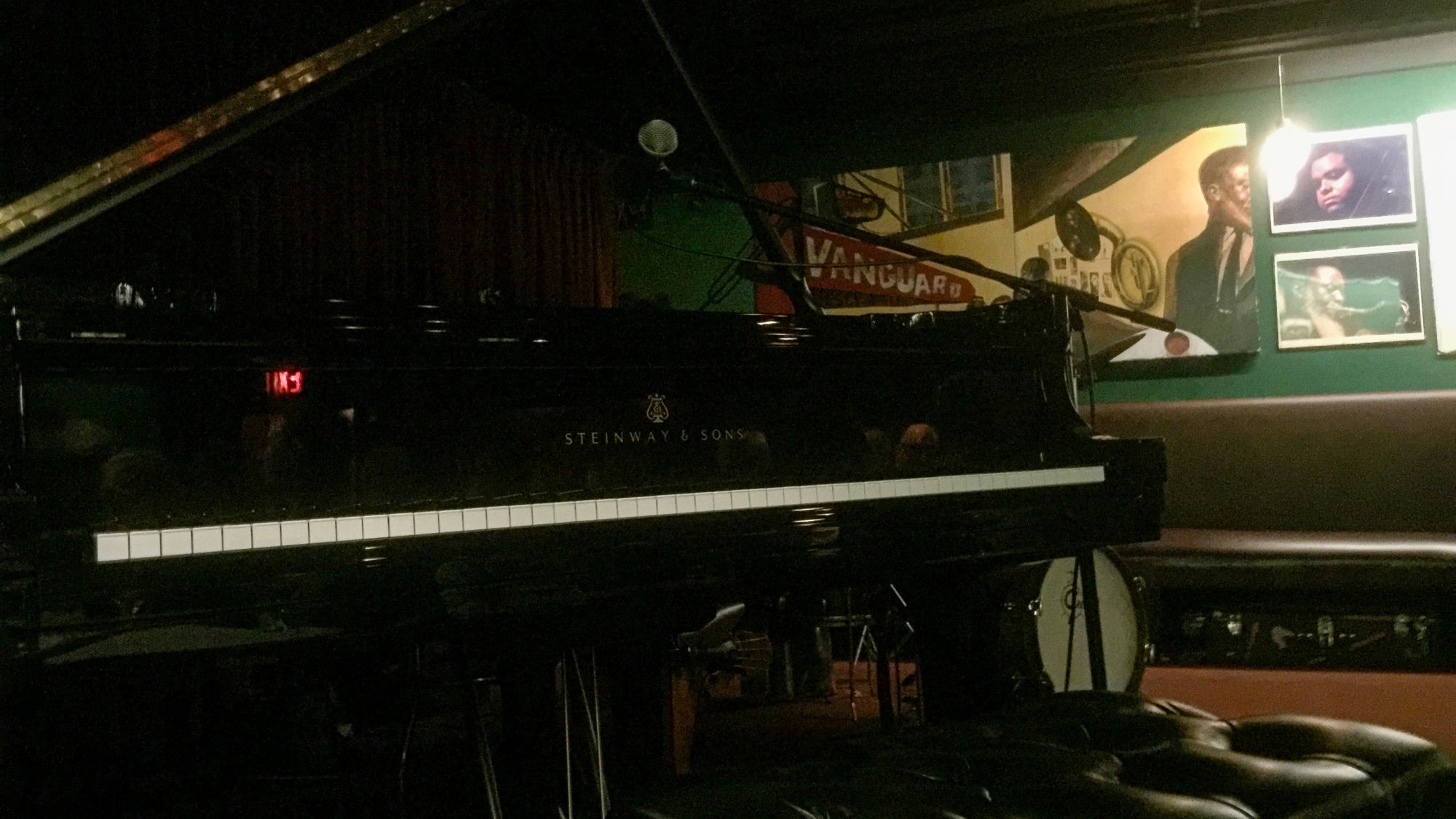

- Barry Harris at the Village Vanguard

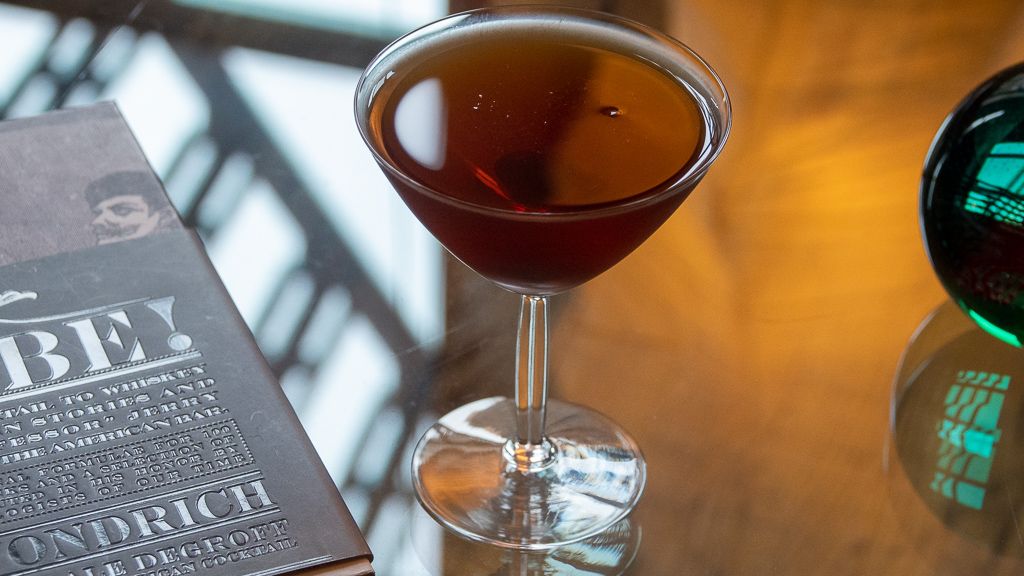

- Friday at five: Rye Manhattan

- Dave Stryker Trio at the Bar Next Door

- One For All celebrates Art Blakey at Dizzy's

We remember our friend the NYC artist Mark Wiener.

As we prepare for our 2021 Polish Christmas Eve Wigilia dinner, we're making some beet kvass, a sour beet tonic that we will use in our barszcz, or Polish beet soup.

For the opening night of Carnegie Hall's 2021-2022 season, Yannick Nézet-Séguin led the Philadelphia orchestra in a performance of Beethoven, Shostakovich, Bernstein, Valerie Coleman, and Imam Habibi.

Our review of the new Indian restaurant Sona, in Flatiron, NYC.

Here's a nice riff on potato pancakes: zucchini pancakes. They're a little lighter, a little sweeter, but still savory and delicious!

A large supply of celery on hand inspired us to make this delicious vegan Sichuan-styled celery stir fry.

The recipe for our favorite sourdough focaccia, which proofs in the fridge for a full 48 hours!

Here's a look at the method we have been using for making sourdough bread for the last four years, along with our current favorite recipe.

These sourdough crackers are addictively satisfying, and are another great use for sourdough starter that you might otherwise discard.

We love making these easy sourdough kimchi pancakes, which are a great use for sourdough starter that would be otherwise discarded.

We paid our final visit to a Midtown East breakfast and lunch favorite Burger Heaven, which is closing this week after 77 years.

We visited the Miami branch of the L'Atelier de Joël Robuchon. How would it stack up the other outposts of the late great chef?

Wiener Krautflerckerl is a classic Viennese dish made with pasta and cabbage. We made our version at home and gave it a Polish twist by using sauerkraut.

Inspired by our dearly departed favorite restaurant, Le Veau d'Or, we made one of their iconic dishers, Céleri Rémoulade.

We take a quick look at vegan chef Amanda Cohen's new vegan burger joint, Lekka Burger.

We look at the the classic cocktail, the Rusty Nail. Is it an "old man drink" and should it be rescued from that status?

This week, we take a look at another classic Scotch whiskey cocktail: the Robert Burns, or the Bobby Burns, or the Bobbie Burns, it gets complicated...

Composting in NYC is easier than you think, even in a small apartment.

A look at the Rob Roy cocktail, invented at the Waldorf Hotel bar in 1894 to celebrate the operetta of the same name by composer Reginald de Koven.

Fasten your seat belts! This week, we take a look at the Gibson cocktail, and how the Plymouth Gibson became my drink.

We do a capsule review of the Midtown East modern Italian restaurant La Pecora Bianca.

Rye and ginger is a classic mixed drink, which can be elevated from old man drink status by using an American straight rye and a good punch ginger beer.

Easy recipe for vegan kimchi.

We visited TacoVision, a new Midtown East taco bar from the team at Crave Fishbar.

We take a look at the Old Pal, a classic equal parts whiskey cocktail from Harry MacElhone of Harry's New York Bar in Paris.

A look inside Vincent Price's classic cookbook, A Treasury of Great Recipes.

We made sauerkraut with beautiful cabbages from the Union Square Greenmarket.

From cultured nyc's Friday at five cocktail series, this week's cocktail is the Sazerac.

How to make homemade yogurt with a sous vide or immersion circulator.

Our review of the Barry Harris Trio at the Village Vanguard.

For the inaugural post of cultured nyc's cocktail column, we take a look at one of the great classics: the Manhattan.

Our review of the Dave Stryker Trio at the Bar Next Door.

Our review of the jazz supergroup One For All and their celebration of Art Blakey's centennial at Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola.